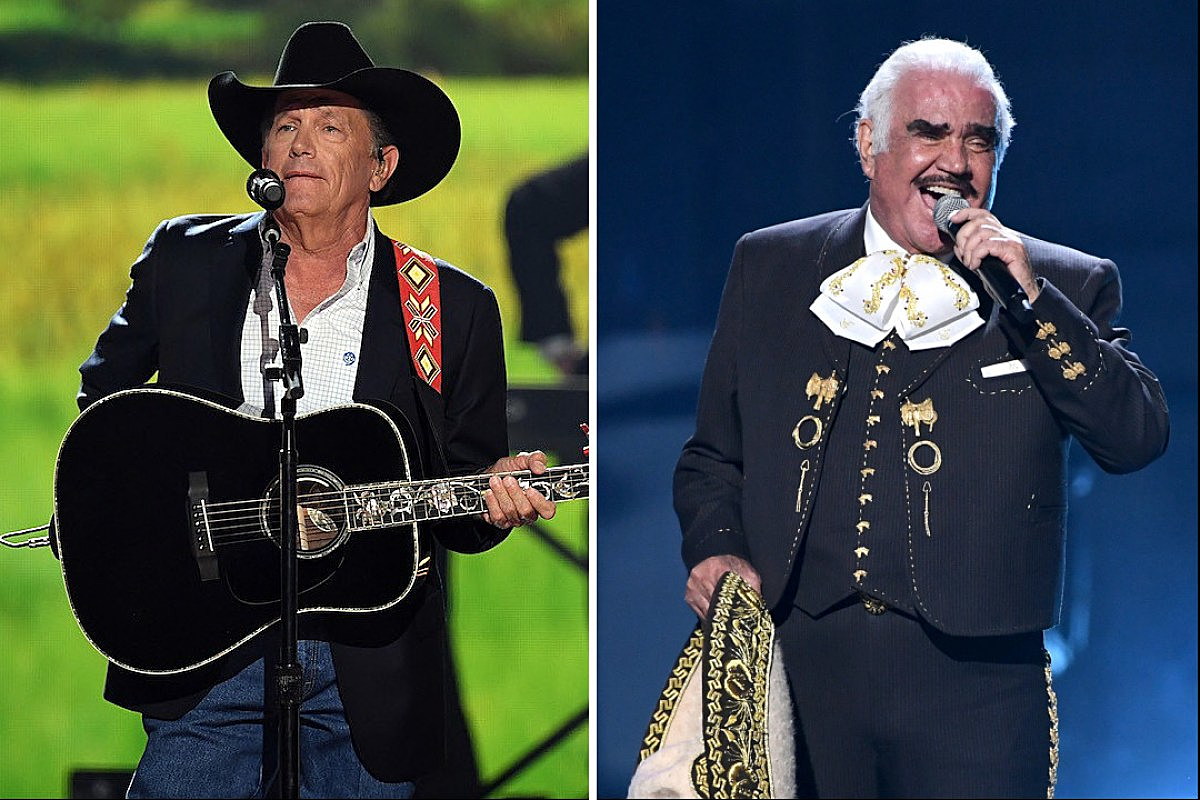

George Strait could remain the unquestioned “King Of Country Music” forever. The reason? It’s not his 44 No. 1 singles on the Billboard Hot Country Songs charts over 40 years. Instead, it’s how he blended country music’s iconic history with the majestic legacy of a now-deceased icon from beneath America’s southern border that has perhaps created an unparalleled standard.

On Sunday, Dec. 12, 81-year-old Mexican ranchera singer Vicente Fernández passed away. Though many country fans nationwide likely are not aware of who Fernandez is, the particular brand of south Texas swagger that is part and parcel to the neo-traditional-to-modern-era macho swagger of Strait, as well as America’s pop and independent-aimed country, Americana, and roots music, owes much to the “Volver, Volver” singer’s work.

“Sad news today. We lost the amazing legendary Vicente Fernández this morning,” Strait tweeted following the announcement of Fernandez’s death. “One of my heroes. May he Rest In Peace and may God bless and comfort his family.”

If one were to categorize this as just a simple tweet without considering the deeper potential impact of Fernandez’s influence on Strait as a larger conversation regarding the past, present, and future of Mexican influences in country music, it’s likely that a critical moment would be missed.

Like Strait in country, Fernandez was the unquestioned ruler of ranchera music. The International Latin Music Hall of Fame inductee sold more than 50 million records and over four dozen gold, platinum, and multiplatinum-selling albums. Ranchera is a genre of traditional, rural-favored Mexican music with roots prior to 1910’s Mexican Revolution that deals largely in tales of love, patriotism or nature.

Mastering the fine art of blending performance and branding has long required unique interplays between established — yet likely little known of regarded by America’s mainstream — minority stars. From his snarl to his gyrating to his cocksure swagger, Elvis Presley owes a debt to Black performers of the 1950s including Big Mama Thornton, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and more. Though “The King” was never known to publicly thank his forebears, Strait now has. That’s important. Digging deeper into how and why Fernandez likely inspired Strait proves fascinating.

As well, it’s important to note that data released in 2016 from the Country Music Association highlights a 25 percent increase in country music’s Hispanic listeners since 2010, plus a note that 7 in 10 non-white adults polled listened to country music once per week or more. However, nearly 25 years have passed since Rick Trevino – an Austin, Texas-born, non-native Spanish speaker who bristled at recording his first album in Spanish because he “didn’t want people to think [he] was a Tejano artist,” achieved a trifecta of hits with “Learning as You Go,” “Running Out of Reasons to Run,” and “I Only Get This Way with You.” His was a much different path one than that of artists like Freddy Fender and Johnny Rodriguez, who found success in the genre during the 1970s as both Tejano and country artists.

At a time wherein embracing representation and equity in country music are important issues to consider, contemplating the who, what, when, where, and why of how culture is authentically transferred into the genre with decency and respect when people may be growing in physical presence and visibility, but not yet ever-present, is essential.

At the center of the Venn diagram of rustic, western charm, unbridled sex appeal, and incredible vocal ability lies the tie that binds Strait’s hero-worship of Vicente Fernandez.

Jessie Katz’s 1999 Los Angeles Times feature on the then 59-year-old Guadalajara, Mexico-native noted that when performing, he was a baritone-voiced singer with long sideburns and a narrow mustache in a “skintight” cowboy suit, a look that excited “bleached debutantes in leopard-skin dresses.” He sang songs that “[embodied] Mexico at its most romanticized — the Mexico of horses and maidens and tequila and cockfights, of honor, love, heartbreak, survival.” In a 2008 concert review, the New York Times’ Jon Caramanica noted his impressive ability to “[hold] a note with operatic grandeur, reducing the audience to mute appreciation.”

Comparatively, George Strait was a western swing devotee born 30 miles south of San Antonio, Texas, roughly 150 miles away from the Mexican border. Outside of both loving more rustic-themed material, even as a young performer, the impact of an artist like Fernandez was apparent. Calling him “America’s latest heartthrob,” a television reporter covering a 1982 concert said that “The singer can make a cowgirl’s jeans twitch at 100 yards.” A fan adds, “[Strait] sings pretty songs and is good looking, too.”

Though 1982 saw romantic singles like Conway Twitty’s cover of the Pointer Sisters’ “Slow Hand” rise up the charts, those were hits more in line with the final years of the countrypolitan era dovetailing with mature rhythm and blues. These are not the same thing as the type of sound that could seduce a debutante – like Fernandez – standing a football field’s length away.

In regards to the more rustic and western aspects of pop stardom shared by Fernandez and Strait, Fernandez once noted that “There are other singers of ranchera music who sing very beautifully but you can tell from the way they sing that they never lived on a ranch.”

Related, in an October 2021 story for the Austin American-Statesman about a Strait appearance at Austin City Limits, a Latino fan of Strait’s noted, “[George Strait] is from Southwest Texas, my [Latino] friends live in a ranch next to his, and thirdly, he’s a great songwriter,” extolling how tied to the intersection of Latino, American, and country cultures Strait remains to this day.

Moreover, Texas has long been the seat of a particular brand of masculinity that is essential to the idyllic notions of manifest destiny and steadfastness associated with both the American dream and related country music. However, the differences between north and south Texas and how those notions nuanced the styles and brands that have played a key role in shaping country music’s mainstream expectation are essential to understanding the importance of a key ingredient of a particular brand of country music’s remarkable and sustained appeal.

The rugged and independent-minded cowboy that pop culture has believed most country music stars to be is a specifically north Texan notion. To wit, Texas cowboys from towns near the northwest Texas’ city of Lubbock named Clarence Hailey Long and Carl “Big-un” Bradley were the inspirations for Marlboro cigarettes’ “Marlboro Man” campaign from 1954-1999.

Comparatively, between 1970-1990, Hispanic or Latino residents grew to represent half to one-in-four residents, respectively of San Antonio and Houston, Texas – two southern Texas cities representing George Strait’s most significant initial fanbases. In regards to how this data could easily impact Strait’s art and presentation, author and academic Amanda Marie Martinez notes, “It’s just natural that that cultural exchange would occur not only around the border but anywhere adjacent to Mexican/Mexican American communities. In Texas especially, where there is such a heavy presence of Mexican/Mexican American identity, of course, it makes sense that George Strait would be a big Vicente Fernandez fan. And the love goes both ways, he’s got a huge Mexican-American fanbase in Texas.”

In 2009, George Strait honored Fernandez by covering his version of Jose Alfredo Jimenez’s ranchera anthem “El Rey.” “What a blast that was. I think it turned out great, and I hope the real mariachis like it. That will be the real test,” he noted to Country Weekly. However, in regards to his status in relation to his hero, Fernandez, the fan-proclaimed “King of Country Music” started, “I can call myself a troubadour, but I can’t call myself ‘the king.’”

Intriguingly, as 2022 looms in the distance, country’s top male stars are as far removed from the genre’s long time macho Texas roots than ever before. Luke Combs is from South Carolina, Morgan Wallen is a Georgian, Chris Stapleton is a Kentuckian, and established icons Blake Shelton and Garth Brooks are from Oklahoma.

During a November 2021 concert at the Ryman Auditorium, Brooks – who himself has sold in the range of 200 million albums and had 19 No.1 Billboard Hot Country Chart hits – stated, “when I was in college, all I ever wanted to be was George Strait. We can talk about ‘The King’ George Strait all night long.”

That lasting impact and influence shows that Strait’s iconic image and personal, partially rooted in Tex-Mex machismo, suggests that Strait could indeed be the “King of Country Music” forever more.