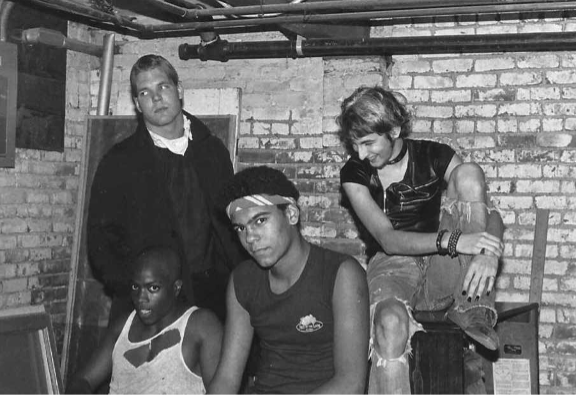

On October 10, Feral House will be publish A Walk Across Dirty Water and Straight Into Murderer’s Row (pre-order here), a new memoir from Oxbow frontman, acclaimed author and Decibel columnist Eugene S. Robinson. Focused on his time growing up in Brooklyn during the 1970s, playing in punk bands and touring the world during the 1980s, the book is an enthralling look at Robinson’s incomparable life. And Decibel is proud to host the following excerpt, which transports readers to genesis of Robinson’s old hardcore band Whipping Boy.

——-

We found out that the guy who had run the Stanford Prison Experiment, Philip Zimbardo, had a son who played bass and lived at the fraternity house where we got our acid. Adam had the extra added plus of also being a New Yorker. And for drums we had the guy who first told me about Steve Ballinger, Dave Nagler. I was never sure if he was a student, older than us by a bit, or really what he was doing at Stanford, but he was alienated as we were, even possibly alienated from us as well, and so we were in business.

One of the hippie Psi Phi co-ops on campus had a basement room where bands could practice for free, and there we went. Playing covers. They played. I just listened. Maybe because that’s what I had always done in the presence of live music. Or maybe because, despite the stage time I had logged, I was unsure of how this was going to go.

Figuring out it was something that happened when Steve screamed at me one night “SING!”

“SING WHAT?” I screamed back. “You’re the SINGER. So fucking SING!!!”

And they started a song we all knew, The Monkees’ “Stepping Stone,” punk-rockized by the Sex Pistols and a band staple since the Teen Idles from D.C. had made it so.

I stepped up to the mic, and though I imagined I was no kind of a stepping stone for the women that had been busy dumping me, I did have some sort of an emotional basis to make this cover feel like more than going through the motions. And like Sinatra once said about being able to tell whether or not you had pulled something off successfully, nobody was laughing.

But in full cart-before-horse fashion and in full consideration of something Steve had that I didn’t—a car—we were at as many shows as we could beg, borrow or sneak our way into. And when people asked who the hell we were, we did what you did back then.

“We’re in a band.”

Six songs does not make a band. A band name is a good start and we were fighting about that. Steeped in the whole Ramones-Zippy the Pinhead thing I thought it made sense to undercut the expected criti- cism we were going to get for being college kids. So, I pushed hard for The Fucking Idiots.

I thought it rolled off the tongue and played against type. Steve took care of that.

“I’m not spending a minute in a band called ‘The Fucking Idiots’,” he groused. “That’s fucking . . . idiotic.”

I was practicing being magnanimous. Or some version of it. “OK. Gimme a name then . . . ”

“Whipping Boy.”

And I believe I actually groaned. Any attempt to go antebellum with this gave me douche chills. One of the benefits of having moved through first disco, then punk rock, then new wave, then hardcore, largely with not a lot of people who knew me or were interested in knowing me, was being able to avoid knowing precisely how stupid the people around me were. But with “whipping” in the title we were virtually inviting some sort of discourse on race politics, and why would I want to put myself in the position of that now being MY problem?

“No no . . . in the old days the servants couldn’t hit the royal kids so they would designate a friend for him or her. If the royal kid fucked up they’d beat his friend. THAT was a Whipping Boy.”

This I liked. I didn’t like the way it looked spelled out, or even saying it. I mean there was a certain élan to BLACK FLAG, but I did like this explanation and so I was sold.

“So what band are you in?”

“Whipping Boy.” And not once did anyone ever tie this into race. Any more than they would have with the whole “Black guy in punk rock” thing.

Which was already the deal at the shows already. The first big show I saw in California I ran into Bill Graham at the front. I recognized him because of Apocalypse Now and here he stood in front of the Califor- nia Hall at a show with Fear, the Circle Jerks and the Dead Kennedys. Punks had driven up from Los Angeles, and down from Reno and Sacramento. It was packed and I’d have presumed Graham would have been happy. But he was not. Especially at being recognized.

“You going to do more punk shows?” I asked, getting ready to work an angle.

“Nah. Too much of a pain in the ass,” he rolled his eyes. Well, it wasn’t the Doobie Brothers but things change.

Getting inside, it was a gathering of the shock troops and it was total

. . . bedlam. But unlike New York where there were not that many places to be from if you were in the places where stuff was happening, no one knew where anyone was from and there was a geo-pecking order with Los Angeles bands being the Alphas and everyone else, like the Adoles- cents once sang, “second best.”

In the midst of what would not too much later be called a mosh pit, there were hundreds of us on the dance floor and it was a melee. Over the heads of the crowd I spied a guy in a black shirt with a big white swastika in the middle and the rockers emblazoned with the words WHITE POWER over and below it.

He saw me see him. My look was judgment-free. Live and let live, or like a friend of mine, a Georgian who had emigrated right when the world was aswirl with the waves of Soviet Jewry getting the hell out while they could: “People can say whatever they want to me, Eugene. But if they put their hands on me . . . ”

Which is right about the time the swastika dude started surfing over crowd top with me as his intended destination. I had always thought West Coast punk rock/hardcore was a little lighter, temperamentally speaking, than New York. I mean it’s hard to street fight when you’re driving to shows. So, I have gotten accustomed to . . . relaxing.

I still had a push dagger inside my engineer boot—young life lessons stick with you—and it was razor-sharp and kept so by not using it for anything that wasn’t business. And this was looking like business.

Given the size of the club there was no need for a circular mosh pit. It was radically random with people bouncing off of each other every which way but I had charted a course that would bring me closer to swastika. I found it always best to deal with problems sooner than later, and as he swam over heads I windmilled through the crowd until we were swinging distance away, and like the butterfly stroke I remember from my days as a swimmer he launched himself over the last row of people between us and as I went to swing for his head, he leaned in and kissed me on the mouth.

Which got from me the only response that made sense. I laughed my ass off and had now officially met Rob Noxious from The Fuck-Ups, a band despised by the folks at Maximum Rocknroll for being “reac- tionary.” While I am sure swastikas and songs like “White Boy” about shooting Latino gangbangers in San Francisco’s Mission District might rub some the wrong way, I couldn’t be made to believe that their “art” was sanction-worthy.

Or put another way and something I’ve said before: they were always nice to me. “They” in this instance being Noxious and the cult of folks that had formed around him who were responsible for a raft of shitty behavior like bathroom muggings, robberies, fights and all manner of drunken excess. But there was not a single one of these folks, many who later became skinheads when that became a thing, who didn’t have an animal understanding of power and violence.

So, when Steve and I started showing up to shows as a duo, me the former competitive bodybuilder and Steve, once voted “strongest hands in Ventura County” on his way to some sort of wrestling championship, well, it just made more sense to be nicer to us than not. Understand that a lot of this . . . punk rock politicking . . . was holdover shit from high school, but when we heard the guys in Crucifix wanted to kick our asses for some reason or another, we went looking for them. We found them at the Elite Club, now the Fillmore in San Francisco, when the ID was finally made, well, yeah. It just made more sense for them to be comfortable competitors (and later friends) rather than for anyone to start swinging.

Besides which, despite my penchant for liking to fight, I had realized something. Mostly that I had been on a steady streak, bodybuilding or not, of getting my ass kicked. Kicked out of Howie’s. Kicked by the three cugines. Punched up at swim meets with the opposing team for G-d knows what reason. Fights during rugby games. The spirit was there but the skill level, well, despite having started boxing at the Boys Club when I was 10 and taking karate and wrestling for a hot minute in high school, just wasn’t.

Mostly because being able to fight is not just about knowing how to fight. It’s maybe most specifically about when to fight. And as for the when, my timing was off. However, the optics were always good enough for us to get dismissed as “jocks,” a sobriquet that never bothered me much. We started hanging out at KPFA, because we liked radio, Tim Yohannon and Jeff Bales seemed like nice guys, and I had an unrequited thing for Ruth Schwartz.

But the whole Stanford athlete thing seemed hard for them to take. We weren’t there to get them to like us though. Neither Steve nor I were that stupid. We were there to figure out the lay of the land and learn what we could.

I don’t know what we learned but it was either enough or not enough so that when the entire band was at a Circle Jerks show one time in 1981, we just decided that we should play it. The end product of high- level LSD-fueled thinking.

“We should be playing this show.” Stated as writ and it just hung there. Steve and I looked around the room, and he nodded at my flight of fancy.

“We should.”

“Fuck it. I’m going to ask them if we can play.”

“Let’s.”

So, we corralled whoever seemed marginally in charge and announced that we wanted to play a few songs before the Circle Jerks came out.

Sizing us up, he folded. Immediately. “If it’s OK with Keith it’s OK with me.”

So, we hemmed up Keith. “Hey man. Let us play three songs before you all play.”

Keith looked at us. The Farm, where the show was, was a ramshackle Quonset hut of corrugated tin, and no security that we could see.

“OK. But you can’t use our equipment. Ask the Effigies if you can use their stuff.”

Tracking down Vic Biondi—who to this day I have a soft spot for because of this—was asked, and considering that they had just played, he was amazingly accommodating, and I don’t say it was out of fear. I don’t say any of them that said yes acted out of fear. Any one thing didn’t seem crazier than any one other thing back then, and since we weren’t asking for money, why not?

“NEXT UP . . . ” the soundboard cat announced, “THE CIRCLE JERKS!

And out we came to an audience of people who while we were unsure WHAT they knew, knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that we were NOT the band announced. The realization of which triggered a fusillade of beer bottles and spit while we played the four, minute-long songs that we knew.

Someone not there or part of this milieu would maybe guess that this response was not what was expected but we had no idea what to expect and were really open to just about anything. There I discovered that I much preferred honest hate than dishonest love.

THAT’s what was happening on stage at the Farm. People hated us, suspected a rip-off was afoot, and in the most direct of ways possible decided to right what seemed to be a sleight-of-hand wrong. All in the face of the reality that no matter how much they hated us, we hated them even more.

Zimbardo was getting punched in the nuts and giving as good as he got while still managing to play a bass that wasn’t his. And our new drummer Dave Owens, who had replaced the old drummer Dave Nagler who had managed to get himself fired for thinking the best place to catch up on the news was during practice from a newspaper on his floor tom, ducked and dodged any and all projectiles thrown at his head.

Owens was a transplant from Augsburg, Germany, and part of the band that “sage” journalists had correctly surmised was “half Black,” and was as unflappable in the face of chaos as I had ever seen. Steve, however, like the Robert Duvall character in Apocalypse Now, had a nimbus of don’t-fuck-around around him, and was relatively untouched as he hunched over a guitar that, given his size, seemed like a novelty shop toy.

And me? I was laughing my ass off and grinning like a madman because my calculus was simple: no one in the building was better armed than I was. Beyond that, there was always the truism that had graced my understanding of the world since I was old enough to be able to ball a fist in anger, and that was the fact that, eventually, I had always imagined, I’d have to kill someone. Never accidentally, or unjustifiably, but nonetheless, dead dead dead.

Now I didn’t think this was that day, but that was mostly because I was having too much fun and the audience, transmuted by all of the crazy, just decided to . . . come along. The hate and the violence became theater and quickly the “set” was done. Zimbardo was stageside making out with a woman he had just kicked in the chest for punching him in the balls. Steve was being fêted on my other side. Dave was grinning like the devil and I was cornered by two guys I didn’t know.

The older impish-looking guy spoke first: “Who ARE you guys?” “Well, we’re,” and I paused because I wanted the name to have

weight when I spoke it, “Whipping Boy.” “I’m Klaus . . . from the Dead Kennedys.”

And the Black cat next to him spoke, half amused, all curious, “And I’m Darren . . . Dead Kennedys too.”

My oh-shit moment was now, as I copped to having met a woman who at first I had mis-remembered as Biafra’s wife before discovering that I was, in fact, talking to her ex-husband in the shape of Klaus. I went on to explain who we were and what we were doing and Klaus asked if we had a tape and in true What Makes Sammy Run fashion I said we had and on the ride back to Stanford, the car was alight with chatter about all the rest of the show and it had been decided that we would record one.

In a scene aswirl with drugs, we had earned an understanding that we were “straight edge,” that bit of weirdness from D.C. promulgated by Ian MacKaye from Minor Threat who, rightly, wanted there to be an alternative to punk rock self-abuse. We were athletes and I didn’t smoke, and had stopped drinking after the drunken incident in New York where, to save whatever the subway cost in 1979, I climbed onto the tracks and crawled under a stopped train. Only to realize that my drunken ass had been on the right side to begin with, and crawled back all while brandishing a knife because: rats.

I later explained to anyone who asked that it was because alcohol had too much sugar in it and I was competing in bodybuilding shows, but the reality was it “made” me an asshole. And very possibly a dan- gerous one to boot.

This is why people thought we were straight edge. However, straight edge doesn’t and didn’t involve gobbling LSD like LSD-gobbling was going out of style. We figured we could do that and still hit the gym. Ian had also done the whole straight edge thing with a twist by making non-fucking a virtue. In literary terms we could call this foreshadowing, since, for some to the manner born, this was never going to work.

The point here though was that we were pretty tuned out to other drugs. The kind you might be on if your father could write scripts and was a noted head guy. Those mooooood drugs.

In any case we had set up to record in some fraternity guy’s room. Kevin McClain, maybe a Theta Delt. None of that shit meant much to me as what was happening on campus had started to mean not much to me. Stanford had become my job and I dutifully applied myself to going to class and putting in the work at school, and my actual job had me comfortably banking on what I had done in New York by way of food service. And realizing that getting laid on the West Coast was not going to be nearly as easy as it was in New York during the late ’70s, I just let them shunt me into the dish room. Perfect place for the antisocial.

I had ponied up some money from washing dishes and between us we had managed to weasel our way into a recording session. Which was going swimmingly until those other drugs had started to kick in and we watched Zimbardo pack up his bass while muttering something. Something about anxiety. Freaking out. Airplanes. Christmas. And just like that, and before I could get my hands on him, he was gone.

When it came time to can the newspaper-reading drummer, it was easy enough: we just stopped calling him. Hip to this, Zimbardo called as soon as he had come back to California. So then there was the whole and breakup thing, which Steve handled with the kind of aplomb that would have eluded a New York native like me whose preferred MO in the face of emotional difficulty is usefully totally absent, or way too direct and hurtful.

There was a friend, though, who in attempting to form a rockabilly band had tracked down some bass-playing cowboy kid from Montana. Honestly, anyone using chewing tobacco would have been a cowboy to me, but tracking down Sam Smoot was easy. Quiet and soft-spoken when he wasn’t, it was an easy sell: “We play hardcore.”

And he was in.

Eugene S. Robinson’s A Walk Across Dirty Water and Straight Into Murderer’s Row is available for pre-order now via Feral House.