1.86.0-2OARUY5K64I6NKUADYKEXMZP4E.0.1-4

Though it may seem difficult to imagine now, at the turn of the millennium, Arch Enemy were not the world-beating commercial juggernauts they are today. The Swedish quintet’s pedigree was unassailable: Michael Amott had helped codify melodic death metal as a genre with his contributions to Carcass’s Heartwork album in 1993. In Arch Enemy, he formed half of a skintight lead guitar duo with his brother, Christopher. Speaking of brothers, drummer Daniel Erlandsson’s elder sibling had helped craft the other melodic death metal ur-text, At the Gates’ Slaughter of the Soul. Bassist Sharlee D’Angelo laid down the low end with both King Diamond and Mercyful Fate, not to mention put in work with Dismember and Witchery.

But those bona fides hadn’t translated to accolades. Though Arch Enemy were massive in Japan, they were slumming it as European tour openers. Part of the problem could be attributed to vocalist Johan Liiva, who was a talented singer but unable to commit to touring. The bigger problem, though, was paradoxically the band’s collective résumés. Arch Enemy’s most notable feature was its members’ other associations; they’d yet to carve out a unique identity.

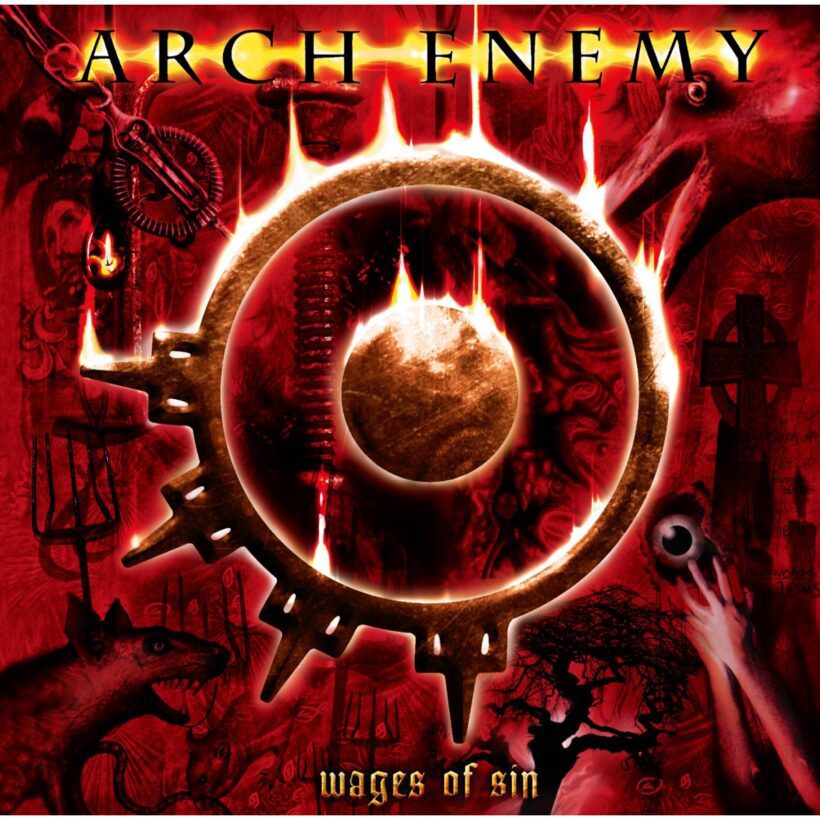

A change was in order: While renegotiating their contract with Century Media, the band parted ways somewhat amicably with Liiva and reconfigured their sound. Drawing inspiration from the European power metal bands that dominated the charts in Japan, Arch Enemy shifted focus to memorability and classic tropes rather than riffs. The Amott brothers tuned up to a relatively legible C-standard and doubled down on melodies and solos. On songs like “Ravenous” and the indomitable “Dead Bury Their Dead,” the band picked up the thread that Chuck Schuldiner laid down when Death covered Judas Priest’s “Painkiller” five years earlier. The result was Arch Enemy’s long-desired commercial breakthrough and the masterpiece of their career: Wages of Sin.

But the band’s most canny maneuver—maybe the smartest and most daring decision they ever made—was enlisting Angela Gossow as their vocalist. Drawing inspiration from death metal’s Floridian founders, Gossow’s furious shrieks delivered all the heft and menace that guitars would have provided in other bands, and then some. In the studio, she pushed the band to strip every ounce of fat from their songs with drill sergeant discipline reminiscent of Henry Rollins. Though she was unassuming at a glance, the Dortmunder proved to be a commanding and imperious performer onstage.

Despite her obvious surplus of talent, Gossow was seen as a high-risk, high-reward choice. To turn that potential weakness into a strength, Arch Enemy concealed her identity and asked fans to guess who she was as part of one of metal’s first viral online marketing campaigns.

Gossow was not the first woman to sing in an extreme metal band—Arch Enemy are quick to reverently cite Nuclear Death’s Lori Bravo and Holy Moses’ Sabrina Classen as predecessors. But with all due respect, she’s the first woman singing in an extreme metal band that broke through the underground, and her undeniable excellence helped inspire a generation of singers including her eventual successor, Alissa White-Gluz.

Female-fronted isn’t a genre, but it is a phenomenon worth celebrating, and that celebration begins with Wages of Sin, the album that helped set the template for melodeath’s commercially unstoppable second wave and gave Arch Enemy an achievement that stands on its own merits.

Need more classic Arch Enemy? To read the entire seven-page story, featuring interviews with the members who performed on Wages of Sin, purchase the print issue from our store, or digitally via our app for iPhone/iPad or Android.